To begin with, writing is not simply about correction; writing is also about composing (that’s why we call this a composition). Unfortunately most teachers and students work on the correction part of the language but have no idea how to teach or learn composing. The result is that you can get, at best, a piece of writing with good English but, overall, it is poor and messy. This article will greatly help teachers and students on that task, so producing good and neat compositions will turn into an easy and quick task. Doubt it? Keep reading.

When writing a composition, most people just sit and start writing, hoping that ideas will flow in the right direction and trusting that they won’t need to make many changes and readjustments. Well, that’s certainly a lot of hope and trust, and even if you manage to write it in one go without having to rewrite parts or start it all again, that way is the easiest way to get a messy and poor composition, and it makes it really difficult to come out with an impeccable or even good piece of writing to impress. But showing how good a writer you can be gets incredibly easier if you follow our 8 steps to write a good composition. The secret for that is just one: plan.

In the first part of this article we learnt how to plan and organise your composition into an outline as the best way to guarantee a neat piece of writing and as a good time-saver. On this second part we will learn how to turn that outline into a composition. So after explaining steps 1-4, here you will learn steps 5-8. Let’s start.

5- title

The most important thing to remember is that a title is not a sentence; it’s only one or several words expressing in a very general way the topic (not usually the approach).

- centre the title on the top line of the paper

- capitalize the first and last words of the title, as well as the most important words (nouns, adjectives, verbs and adverbs). Don’t capitalize grammatical words (prepositions, connectors, articles, etc.) except if they start or finish the sentence or they go after a colon (:)

- if a quotation appears in the title, use a capital for the first word in the quotation

- don’t write a sentence (subject+verb+complements) as a title and don’t finish the title with a stop (.)

- don’t underline a title

Example of a good title: Life in a Village

Examples of bad titles:

- Life in a village. (no final stop, “Village” needs capitalization because it’s a noun and also the last word)

- I prefer to live in a village. (no final stop, “Prefer” “Live” and “Village” must be capitalized; this is a sentence, with subject, verb and a complement, so it’s wrong for a title)

- a Village: the Best Place to Live (“A” needs capitalization because it begins the title, also “The” because it goes after a colon, and titles shouldn’t be underlined)

6- organize ideas into paragraphs

6- organize ideas into paragraphs

A composition must be organized in different paragraphs. In formal writing for publication (books, magazines, newspapers, etc) every paragraph must be indented (the first line starts 3-5 spaces more to the right than the rest of the lines). In other cases it is more common to simply use a double space to separate one paragraph from the next (leave one or two empty lines in between), so you don’t need indentation but paragraphs are also well defined, separated (as you can see in this article).

The paragraphs are used to group ideas into units and must contain more than one sentence. The first paragraph begins with the opening sentence and it is the introduction, the first contact we have with the topic, so we usually put there the most relevant, shocking or interesting information to catch the reader’s attention or to make them understand the situation.

The last paragraph ends with the closing sentence and it is the conclusion. Depending on what kind of composition we’re writing, we use the last paragraph to explain the result of the event, the end of the action, the conclusion of our reasoning, the climax of the story, our personal opinion, etc. (In case of doubt, giving your personal opinion on the topic is always an easy way to finish a composition).

We have to choose, from the points we defined in step number 2 (see part 1 of this article), which ideas are best for the first paragraph and which are good for the last paragraph. The rest of the points will go in one or several paragraphs in the middle (in the “body” of the composition). Every paragraph contains one or several points, but all of them must be talking about the same general idea, and that idea must be a bit (or very) different from the general ideas of the other paragraphs. That is what makes a paragraph a unit.

Example:

We will continue using the same example we proposed for steps 1-4 in our previous article:

Topic- Life in a village

Approach- better than cities

In the first paragraph we start with the opening sentence and then we can talk about the bad things about living in a city. That way, the good things about a village will later sound even better.

Another paragraph may talk about people and why they make life there better (they’re nice, they know you, care about you and help you).

Another paragraph may talk about life there being more natural (clean air, no pollution, contact with nature, beauty of the landscape, more animals).

And another paragraph may talk about the way of life (everything cheaper, healthy entertainments, more exercise).

The last paragraph is going to end with the closing sentence. The other sentences in this paragraph may reinforce the closing sentence or it may be one or several points that will help us accept the idea in the closing sentence better. For instance, if the closing sentence is a look to the future (“I have decided to move to a village”) then the previous sentences in that paragraph may explain that in the last months I’ve been getting more and more tired of cities.

7- write the composition

Now that you’ve got your opening sentence, your closing sentence, your points and the organization of your points into paragraphs, it’s time to finally write the composition. Notice that for most people this step is the only one they actually make, but for a good writer this step is only the unfolding of the whole structure already constructed, so it becomes easy, quick and solidly grounded.

Now that you’ve got your opening sentence, your closing sentence, your points and the organization of your points into paragraphs, it’s time to finally write the composition. Notice that for most people this step is the only one they actually make, but for a good writer this step is only the unfolding of the whole structure already constructed, so it becomes easy, quick and solidly grounded.

It is very important to use connectors to relate ideas (although, nevertheless, that’s why, so, because, afterwards, in the first place, on the one hand, unfortunately, etc.). But always remember that the English language doesn’t like long complicated sentences, so, as a general rule, use compound sentences but short and with only two or three elements (main clause + subordinate/coordinate clause)

Example of a nice sentence: Cities are getting more and more aggressive, that’s why I’m thinking of moving to a village.

Example of a clumsy sentence: I don’t like cities because, after all the changes in modern societies, they are getting more and more aggressive and polluted, as everybody can see, although I know that on the other hand, life in a city offers more opportunities for some things such as jobs and entertainments, but the good things don’t compensate for the bad things, so that’s why I’m thinking of moving to a village, since life in a village is much better, natural and healthy than life in a city, especially big cities, which are still growing with more and more new people coming to live there.

A student of English may be impressed by the second example, they might think that with sentences like that you can prove that your level of English is much better than with the first example, but remember that, when we’re writing a composition, style is very important, not just grammar and correction. Besides, the closing sentence in that example is not the right one for the topic we’re writing about. A native reader would feel that the second sentence is really too long, too complicated, too difficult to understand and too horrible! English likes its sentences short and clean. If you want to express all the ideas from the second example, break it down into different sentences, shorter and more simple, for example like this:

“Everybody can see that, in modern societies, cities are getting more and more aggressive and polluted. It is true that, in big cities, the suply of jobs and entertainment is much bigger; nevertheless, the good things don’t compensate for the bad things. I really believe life in a village is much better, natural and healthy than life in a city, that’s why I’m thinking of moving to one.”

Now we expressed the same ideas but using simple structures. Connectors (underlined here) are showing the relationship between the different ideas, and they are a must (obligatory) in your compositions, but using lots of connectors will make the text look clumsy and overloaded. In the last example we only used two connectors for the conclusion paragraph. Using four connectors there would probably be too much. So try to balance your need to show how much you know, with the need to show how good a writer you are.

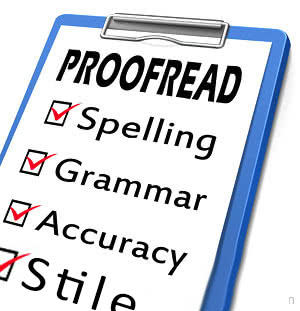

8- correct your composition

8- correct your composition

You need to leave time at the end to read your composition carefully one or several times (usually 2 times is enough, more can end up confusing you). Remember that the mistakes you don’t correct, will be corrected by the evaluator, so try to see your mistakes before the evaluator sees them. Read your composition as if you were the evaluator reading someone else’s composition.

IMPORTANT: Planning your composition is the best way to get a fine result. It is very difficult to write a good composition without planning it first, and the planning will also save you time! As a general rule, use about 15% of the time working on the planning, 75% writing your composition and 10% revising and making corrections. But you might need to increase or reduce those percentages, so practise and see how much time you need for it. If you have 30 minutes to write a composition for an exam, 5 minutes for the planning would be the rule, but maybe you need a bit more or less time for it. Put these instructions into practice and see what is best for you. Also save about 5 minutes for the corrections at the end. But if you think that not doing the planning is going to save you time, you will find out that a good composition written in 20 minutes is much better than a bad composition written in 40 minutes, so make the outline!

FURTHER ADVICE: don’t use contractions if it’s a very formal piece of writing, but do use them a lot if it’s something informal (letter to a friend, etc). Try to make your writing tidy. If you are messy (and have enough time), you can write it in rough and then make a fair copy of it. If it’s hand-written, try to have a readable handwriting. If there is a limit of words you must write, respect that limit (usually, a variation of 10% above or below that limit is acceptable, but ask your teacher). If there is a limit of time, check the time frequently and make sure you hand in your composition before the time is over. If there is a limit of words you don’t need to be counting your words every 2 minutes: write a few lines in English, count the words and find out how many words per line is your average. If you get 10 words per line, then for a composition of 120 words you know you need to write 12 lines. Dot 12 lines and you’ll see how long your writing must be without the need of wasting time counting and checking constantly. In the rare case that your teacher requires precision in the number of words, you can bother to count the exact number of words only when you are near the end of your 12 lines, but ask him or her how precise they want you to be with the count.

APPENDIX

CONNECTORS

Connectors are grammatical words used to relate two sentences and express a new idea. They can be “conjunctions” or “free connectors”. The difference between them is this:

- conjunctions- they join two simple sentences to make a complex sentence

I phoned you. She came home. (two simple sentences)

She came home AFTER I phoned you. (one complex sentence made up with a conjunction)

- free connectors- they relate two simple sentences but keep them separate.

I phoned you. THEN, she came home. (two simple sentences related chronologically by a free connector)

So free connectors can express the same relationship as a conjunction but using a different construction (in two sentences, not in one). Free connectors are not part of any of the two sentence and they are usually separated from both sentences by stops and commas.

Use connectors suitable for your level (“and, but, so, because” is alright for beginners, but higher levels need more variety). Free connectors are usually better for writing than conjunctions, more formal.

I like villages but I live in a city – (conjunction- a simple connector) ok for beginners

I like villages although I live in a city – (conjunction- a more formal connector) shows higher level

I like villages. Nevertheless, I live in a city – (free connector- higher level, more elegant and makes your composition nicer for a formal composition, but not for informal writing)

For more information about connectors check our grammar file: The compound sentence- connectors.

For more information about specific connectors go to our grammar section and filter the results by “connectors” (first box).

All the steps explained here are generally good for most kinds of compositions, but depending on the topic you write about, you may need to adapt and modify some details. For example, if you are writing about the difference between the city and the countryside, everything said here is perfect. But if you are writing about your last holidays, the organization of paragraphs (step 6) will usually follow a chronological order, so you don’t have to think where every point goes.

Written by Angel CastaŮo